Best Management Practice Fact Sheet 3: Grass Channels

ID

426-122 (BSE-271P)

EXPERT REVIEWED

This fact sheet is one of a 15-part series on urban stormwater management practices.

Please refer to definitions in the glossary at the end of this fact sheet.

Glossary terms are italicized on first mention in the text. For a comprehensive list, see Virginia Cooperative Extension (VCE) publication 426-119, “Urban Stormwater: Terms and Definitions.”

What Is a Grass Channel?

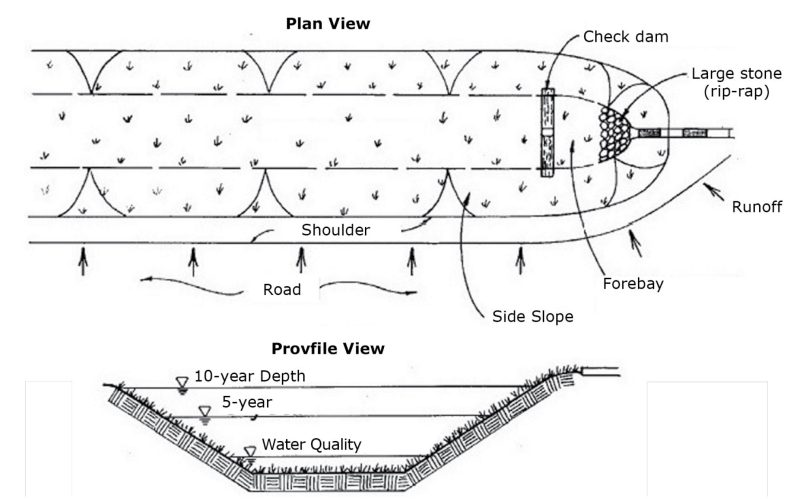

Grass channels (GCs) are wide, gently sloping, open channels with grass sides used as a stormwater conveyance system (see figure 1). GCs are similar to ditches; however, their side slopes are much more gradual. GCs provide treatment via filtering through vegetation. When compared with traditional curb and gutter, or inlets and pipes, which remove no pollutants, GCs may provide a modest amount of runoff reduction and pollutant removal. The extent of this reduction depends on the underlying soil characteristics, slope, and flow velocity. At higher velocities, stormwater is only conveyed and is not treated. Unlike dry swales, (VCE publication 426-129), GCs do not include a soil media and/or specific storage volume.

Where Can Grass Channels Be Used?

Residential, commercial, and industrial areas are all good candidates for GC implementation. GCs are limited to small drainage areas (smaller than 5 acres) with any type of underlying soil. However, a soil amendment, such as compost (see VCE publication 426-123), is recommended for hydrologic soil group (HSG) C or D to improve infiltration.

Highways and parking lots are well-suited for GCs, as are turf areas, such as golf courses, sports fields, and residential lawns. While the objective of both dry and wet swales (VCE publication 426-130) is retention and runoff reduction, the main purpose of a GC is to transport stormwater from one place to another.

How Do Grass Channels Work?

As an engineered best management practice (BMP), GCs mainly convey stormwater to a stormwater treatment practice, but they can provide modest water quality improvement with a slight reduction in volume. Concentrated runoff is initially directed over a check dam that reduces flow velocity and maximizes vegetative filtering during conveyance. The grass lining protects the conveyance system from erosion by reducing velocities and provides minor filtering and infiltration. The GC then transports stormwater to another BMP for further treatment (see figure 2). In terms of water quality, the vegetation in the channel will also filter the stormwater and remove a small portion of nutrients, often those that are attached to sediment.

Selection of grass type may depend on local climate and tolerance for moist conditions. Creeping bentgrass is a reasonably water-tolerant species for cool-season grasses, as is bermudagrass for warm-season grasses. Both can be obtained from seed or sod throughout Virginia.

Limitations

- Not recommended for channels with greater than 4 percent slope; otherwise, erosion will likely occur in the channel.

- Not suitable for drainage areas of 5 acres or larger.

- High-density residential lands may concentrate run-off and result in excessive channel erosion.

- Channel must remain above the seasonally high water table to preclude groundwater contamination or design failure.

Maintenance Routine Maintenance

(annual)

- Remove trash, debris, and accumulated leaves, which can clog the channel.

- Monitor channel bottom for excessive erosion, braiding, ponding, or dead grass.

- Inspect side slopes for evidence of erosion.

- Replant to maintain 90 percent cover; reseed any areas with dead vegetation.

- Look for bare soil patches or sediment sources in the contributing drainage area and repair.

- Mow regularly. GCs are typically mowed seasonally at a tall grass setting to prevent taller shrubs and trees from taking hold in the channel. Frequent, manicured mowing at low settings is not recommended and can lead to erosion of the channel.

Nonroutine Maintenance

(as needed)

- Repair check dams, remove any accumulated sediment from behind dam structure.

- Remove sediment buildup within the channel.

Performance

Grass Channels are effective at removing small concentrations of pollutants from incoming water flow. A typical GC is expected to reduce total phosphorus (TP) by 25 percent and total nitrogen (TN) by 35 percent, including mass load reduction from runoff removal. More advanced designs can be achieved when using very long travel paths within a GC or soil amendments to enhance infiltration. These advanced designs may lead to higher runoff reductions (VA-DEQ 2011).

Expected Cost

Grass channels are a relatively inexpensive stormwater treatment practice when compared to other alternatives. Construction costs of grass swales average approximately $4.60 per ft2 of surface area. Operation and maintenance costs can be estimated at $0.50 per ft2 of surface area on an annual basis (Washington State Department of Ecology, & Herrera Environmental Consultants, 2012).

Additional Information

The Virginia departments of Conservation and Recreation (VA-DCR) and Environmental Quality (VA-DEQ) are the two state agencies that address nonpoint source pollution. The VA-DCR oversees agricultural conservation; VA-DEQ regulates stormwater through the Virginia Stormwater Management Program.

Additional information on best management practices can be found at the Virginia Stormwater BMP Clearinghouse website at https://www.swbmp.vwrrc.vt.edu/ (Permanent link: https://perma.cc/WC5L-KCZ8). The BMP Clearinghouse is jointly administered by the VA-DEQ and the Virginia Water Resources Research Center.

Online Resources

Chesapeake Stormwater Network – http://chesapeakestormwater.net/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/02/DCR-BMP-Spec-No-10_DRY- SWALE_Final-Draft_v1-9_03012011.pdf

Knox County Stormwater Management Manual – https://www.knoxcounty.org/stormwater/manual/Volume%202/Volume2Combined.pdf (Permanent link: https://perma.cc/JS56-A9MT)

Virginia Stormwater BMP Clearinghouse – https://www.swbmp.vwrrc.vt.edu/ (Permanent link: https://perma.cc/WC5L-KCZ8)

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources – https://dnr.wi.gov/topic/stormwater/documents/VegetatedSwale1005.pdf

Companion Virginia Cooperative Extension Publications

Daniels, W., G. Evanylo, L. Fox, K. Haering, S. Hodges, R. Maguire, D. Sample, et al. 2011. Urban Nutrient Management Handbook, VCE Publication 430-350.

Fox, L. J., Sample, D. J., Robinson, D. J., & Nelson, G. E. (2018). Stormwater Management for Homeowners Fact Sheet 4 Grass Swale. VCE Publication SPES-12P.

Gilland, T., L. Fox and M. Andruczyk. 2018. Urban Water-Quality Management - What Is a Watershed? VCE Publication 426-041.

Sample, D., et al. 2011-2012. Best Management Practices Fact Sheet Series 1-15, VCE Publications 426-120 through 426-134.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express appreciation for the review and comments provided by the following individuals: Timothy Mize, associate Extension agent, Virginia Tech; Stuart Sutphin, Extension agent, Virginia Tech; Mike Goatley, Extension specialist and professor, Virginia Tech; Stefani Barlow, undergraduate student, Biological Systems Engineering, Virginia Tech; and Richard Jacobs, conservation specialist, and Greg Wichelns, district manager, Culpeper Soil and Water Conservation District.

References

Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (VA DEQ). 2011. Virginia DEQ Stormwater Design Specification No. 3: Grass Channels, Version 1.8. https://www.swbmp.vwrrc.vt.edu/wp-content/ uploads/2017/11/BMP-Spec-No-3_GRASS-CHANNELS_v1-9_03012011.pdf.

Washington State Department of Ecology and Herrera Environmental Consultants. PugetSound Stormwater BMP Cost Database. 2012.

Glossary of Terms

Best management practice (BMP) – Any treatment practice for urban lands that reduces pollution from stormwater. A BMP can be either a physical structure or a management practice. Agricultural lands use a similar, but different, set of BMPs to mitigate agricultural runoff.

Braiding – A phenomenon when streams or channels incur bottom erosion to form smaller channels that intertwine.

Check dam – A small structure, either temporary or permanent, usually made of stones or logs and constructed across a ditch, swale, or channel to reduce concentrated flow velocity.

Dry swales – Shallow, gently sloping channels with broad, vegetated side slopes and low-velocity flows. They are always located above the water table to provide drainage capacity.

Erosion – A natural process by either physical processes, such as water or wind, or chemical means that moves soil or rock deposits. Excessive erosion is considered an environmental problem that is very difficult to reverse.

Grass channels – Open channels with grass sides that convey runoff with modest velocities while improving runoff quality.

Groundwater contamination – The presence of unwanted chemical compounds in groundwater. In the case of infiltrative stormwater treatment, it would normally refer to dissolved compounds, such as nitrates.

Hydrologic soil group (HSG) – Classes of soils (named either A, B, C, or D) that indicate the minimum rate of infiltration observed after prolonged wetting time.

Impervious surfaces – Hard surfaces that do not allow infiltration of rainfall into them; not pervious.

Infiltration – The process by which water (surface, rainfall, or runoff) enters the soil. Nutrients – The substances required for growth of all biological organisms. When considering water qualities, the nutrients of Nutrients – The substances required for growth of all biological organisms. When considering water qualities, the nutrients of greatest concern in stormwater are nitrogen and phosphorus, because they are often limiting in downstream waters. Excessive amounts of these substances are pollution and can cause algal blooms and dead zones to occur in downstream waters.

Pervious – A ground surface that is porous and allows infiltration into it.

Sediment – Soil, rock, or biological material particles formed by weathering, decomposition, and erosion. In water environments, sediment is transported across a watershed via streams.

Soil amendment – Any material mixed into the soil; usually compost, to improve overall soil quality.

Stormwater – Water that originates from impervious surfaces during rain events; often associated with urban areas. Also called runoff.

Stormwater conveyance system – Means by which stormwater is transported in urban areas.

Stormwater treatment practice – A type of best management practice that is structural and reduces pollution in the water that runs through it.

Watershed – A unit of land that drains to a single “pour point.” Boundaries are determined by water flowing from higher elevations to the pour point. A pour point is the point of exit from the watershed, or where the water would flow out of the watershed if it were turned on end.

Water table – The depth at which soils are fully saturated with water.

Wet swales – Shallow, gently sloping channels with broad, vegetated side slopes constructed to slow runoff flows. They typically stay wet by intercepting the shallow groundwater table.

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and local governments, and is an equal opportunity employer. For the full non-discrimination statement, please visit ext.vt.edu/accessibility.

Publication Date

July 1, 2020